West Papua

Though no longer home to the cannibals and headhunters it was once famous for, the Indonesian half of the island of New Guinea still offers plenty of opportunities to go where few have gone before among some of the most exotic cultures, spectacular scenery and challenging trekking terrain in the world.

Introduction

New Guinea, just north of Australia across the Torres Strait, is the world’s second-largest island. Its dense rainforests, the largest in the world after the Amazon, and its almost impenetrably rugged mountainous terrain ensured that throughout its history almost every tribal group remained fairly isolated even from its closest neighbours (although a certain amount of trade between groups did occur). As a result the island has around 1,000 different languages, one fifth of the world’s total.

The eastern half of the island is an independent country called Papua New Guinea. The western half is an unwilling province of Indonesia called West Papua. Papua New Guinea is by far the more developed and very few locals wear anything other than western dress these days whereas in remote parts of West Papua a few people can still be seen wearing traditional (un)dress during everyday life.

As an example of just how isolated some parts of West Papua still are, cannibalism and tribal warfare continued in parts until the 1990s and there are still unconfirmed rumours among loggers and gold prospectors of encounters with naked nomadic tribes in the depths of the Mamberamo. In 2006 a scientific expedition flew by helicopter into a valley in the Foja Mountains that was so remote it had never been accessed even by locals. Dozens of new species of animals were discovered that had evolved in isolation from humans and as a result were unafraid to walk right up to researchers.

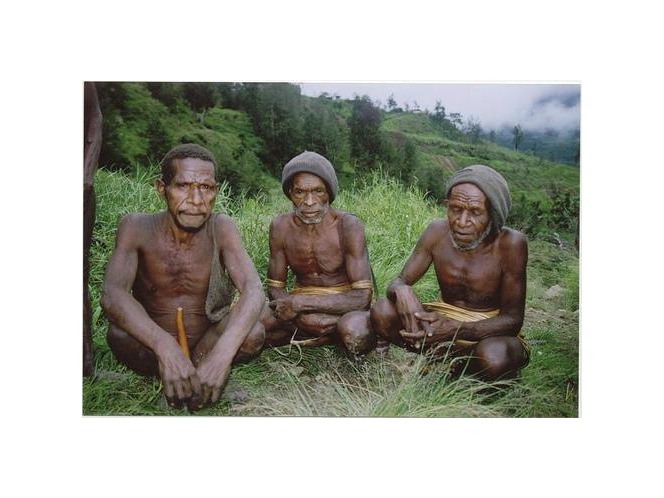

As a tourist, however, you will be disappointed if you come to West Papua expecting to see “Stone Age” tribes. Even in Yali country, the most traditional part of the Highlands, only about 10% of people still wear the traditional penis gourds (kotekas) or women’s bark dresses. In the Korowai area in the South of West Papua the number is higher but in general western clothing has made inroads everywhere. If you can ignore that though you will have a great time: the culture is still extremely traditional, the scenery is spectacular and the locals are friendly and in some parts still very surprised to see outsiders.

In the Mamberamo area in the north of Papua that was until recently closed to tourists there are, as mentioned above, rumours about “uncontacted” tribes, although the veracity of these rumours is hotly debated. In general Mamberamo villagers all wear western dress, although they may strip it off to go hunting in the jungle.

Be warned: if you see any organisation offering “First Contact” tours it is a scam. If you spend some time in West Papua, know Indonesian and make friends with locals you may find people willing to tell you their stories of being paid by tour companies to dress up as the supposed “uncontacted” tribe. There are plenty of them around.

If you see photos where large numbers of people are all wearing traditional dress, this means they were either taken at least a decade ago or the people dressed up especially for that photo.

History

New Guinea has been inhabited by Melanesians for 40,000 years and its people developed agriculture at a very early stage, at least 10,000 years ago. In more recent millennia Austronesians arrived from South East Asia and settled the coastal regions of New Guinea, maintaining a certain amount of trade with nearby parts of Indonesia and with the tribes of New Guinea’s interior. New Guinea was first sighted by the Portugese in 1511 and landed on by the Spanish in 1545. Since then various parts of it have been under Spanish, French, British, German, Australian, Dutch and, today, Indonesian rule. However, in practice even the coastal inhabitants of New Guinea had no real contact with Europeans until 1855 when some Dutch missionaries arrived.

The first Dutch posts were set up in the far north and south of the island in the late 1890s and early 1900s and the capital Jayapura, then called Hollandia, was established in 1910. In the 1920s a few groups of explorers had some very brief contact with the Dani people of the Baliem Valley in the Central Highlands but the area was not properly explored until 1938 when the Baliem Valley, an area that had previously been assumed to be uninhabited, was shown to be home to 100,000 “uncontacted” Dani tribesmen. However, no missionary post was set up in the Baliem Valley until 1954 and the first missionaries reached the neighbouring Yalimo in 1961. A government post was set up at Angguruk, the largest village of the Yalimo, in 1968. Since then all the tribes of the Central Highlands have been baptised, although the new religion remains mixed somewhat with some older pre-Christian beliefs. There are still people in the Yalimo who remember seeing those first white men walking down from the mountains into their village.

After the Dutch gave up Weat Papua it quickly went over to Indonesian control after a very controversial vote in 1969, a move very unpopular with West Papuans who are ethnically and linguistically completely unrelated to Indonesians. A guerilla separatist movement, the OPM, has been operating in the interior ever since. Also since then the government has moved hundreds of thousands of migrants in from other parts of Indonesia and along with America has been busy extracting West Papua’s very rich resources (gold, silver and copper) while the people remain the poorest in Indonesia.

Until 2001 it was called Irian Jaya, although this name is very unpopular among locals who prefer West Papua. Confusingly, since 2003 West Papua has also been officially divided into two Indonesian provinces: West Papua and Papua.

Travel

The first thing to know about travel in West Papua is that everything (guides, transport, permit) can be arranged very quickly and easily upon arrival even if you don’t speak a word of Indonesian. DO NOT on any account think that it’s necessary to book one of those ridiculous adventure tours sold on the internet or by travel agencies for thousands of dollars. In a place as undeveloped and with as few facilities as West Papua, tour companies really can’t offer you anything that you can’t just arrange yourself the same day you arrive.

One very important thing to note is that when applying for your visa, some Indonesian embassies such as the one in London will tell you that it’s impossible to go to West Papua as a tourist. I have no idea where they get this rubbish from but just DO NOT write on your visa application form that you plan to visit West Papua. No one will stop you anywhere and on arrival in West Papua the police will happily issue you your surat jalan (travel permit – see below) which is all that you need to travel freely in West Papua. If, however, you write on your Indonesian visa application form that you plan to visit West Papua, some embassies may put a stamp on your visa saying “Not valid for travel to West Papua.”

The majority of tourists will fly into Sentani, the town where the airport is next to the capital, Jayapura. It is also possible to arrive at Timika and Merauke. Airlines such as Garuda, Lion Air and Merpati all fly to West Papua daily and Pelni has a few ships running here from other parts of Indonesia too.

Once you arrive in Sentani you should go to the nearest police station and pick up your surat jalan (travel permit for the interior of West Papua). It’s just a formality and requires just a few passport photos and a fee (US$5-US$20 depending on your haggling skills).

If you want to do a trek in the Central Highlands such as from the Baliem Valley to the Yalimo and maybe even on to Mek territory you will need to fly from Sentani to a town called Wamena in the Baliem Valley, the largest town in the interior. Only one road goes from the North to the Highlands. It leads from Nabire in the North (accessible by flight or 36-hour ferry from Jayapura) to Enarotali in the Western Highlands (unconnected to Wamena by road). This road is often unpassable. Shop keepers in Nabire or Enarotali should be able to tell you if anyone is planning to drive it soon.

The airline that flies to Wamena is called Trigana and has several flights every day. I never had problems just turning up and getting a seat on the same day but perhaps if you are flying around holiday time you should leave a day or two spare on either side. It costs about US$100 each way.

Once in Wamena lots of English-speaking guides will approach you. Some are quite dodgy so make sure you get one recommended by your hotel in Wamena. Many try to get you to pay for a guide plus a porter plus a cook but of course all that is really not necessary. Your guide should be able to cook for you and carry your bag. The total cost of a trek organised upon arrival in Wamena should be US$60 a day including food for you and your guide. Insist on paying him his daily fee and paying for food (fruit, veg, potatoes, rice, noodles) and accommodation yourself in villages during your trip. Don’t agree to scams such as giving him the money and letting him take care of everything, paying him in advance or paying him extra to take you to an extra-remote place.

If you speak Indonesian you can go out to the villages by public transport and hire a local to be your porter. These non-English speaking locals will be far more honest than the Wamena guides mentioned above. This way maximum total costs per day during your trek should be US$40 (see Baliem Valley page for breakdown).

If you want to visit the famous tree house-dwelling Korowai tribe in the south of West Papua, an entire 2-week trip starting and ending in Sentani with an English-speaking guide should cost US$1500 if flying to Dekai then traveling by local boats to the start point of your trek. Again, this could be slightly cheaper if you speak Indonesian and do not need a guide from Sentani. If that is so, fly to Dekai yourself and catch local boats to Mabul or Yaniruma, good starting points for Korowai treks, and find a local to guide you from there. It is also possible to trek to the Korowai from the Baliem Valley in about a month.

The Korowai area is the most traditional in West Papua. It’s also extremely hard to get around in and requires time for waiting for boats unless you want to charter your own which is almost prohibitively expensive. Indonesian language or an English-speaking guide are essential. Many Korowai still wear traditional (un)dress, live in tree houses, are semi-nomadic, still unchristianised and don’t speak Indonesian. They are not, however “Stone Age”, “Cannibals” or “Uncontacted” as some tour agencies make them out to be.

The border with Papua New Guinea also has some remote groups who wear traditional dress but getting here is extremely hard. The part of the south around Agats (accessible by river from the Korowai area via the town of Senggo or by plane from Timika) is famous for the traditional art of the Asmat people although they now dress in Western clothing. The North coast and Bird’s Head Peninsula have great diving, bird watching and trekking.

The rest of this site is dedicated to trekking in the mountainous, jungley Central Highlands. You can follow the links below for information and advice on individual areas but remember any trek there will have to start from Wamena in the Baliem Valley, which you can fly to from Sentani, West Papua’s main airport with lots of daily flights from elsewhere in Indonesia.

Leave a Reply