Sinsk and the Lena Pillars, Yakutia

The Lena Pillars near Sinsk village, Khangalas District, Yakutia

The appearance of the Lena Pillars, a forest of rock fingers up to 220 meters tall lining the river banks, indicated that we were approaching Sinsk as our motorboat skimmed over the surface of the Lena, at 4,400 km the longest river in Russia.

Sinsk, the village where my wife’s parents live in the Republic of Yakutia, is located 230km from Yakutsk on the banks of the River Lena. It is classed as a «hard-to-access» settlement, as it has no road and no airport. You can get there only by boat in summer or by driving on the ice in winter. In spring and autumn there is a period of about a month when the ice is too thin to drive on but too thick for boats. At this time Sinsk and many other villages throughout Russia are completely isolated from the outside world. There are even big cities that cannot be accessed overland, although they of course have the blessings of airports, unlike Sinsk.

Trips like this remind you of what it is easy to forget when sitting at your desk in Moscow: Russia, at its central latitudes, is basically one big forest. Almost a quarter of the world’s trees are located here and the country’s total forest cover area is bigger than the entire USA. The edges of many settlements are defined by the point where the houses end and the trees take over. Between villages there is nothing but unbroken forest, sometimes for hundreds of kilometers. Yakutia has a population of only 1 million, of which 350,000 live in the capital Yakutsk, leaving the rest of the India-sized republic is very sparsely populated.

Inhabitants of Sinsk village, Khangalas District, Yakutia

Through this vast forest sneaks the Lena until, like the other two great Siberian rivers the Ob and the Yenisey (and the other great Yakutian rivers, the Yana, the Indigirka and the Kolyma), it breaks out of the taiga forest and into the treeless tundra that covers Russia’s most northern latitudes, eventually emptying into the Arctic Ocean.

Despite being such a huge geographical feature of the country, few Muscovites spare a thought for it or for the hundreds of thousands of peripheral lives lived out on its banks by citizens of Russia – the city dwellers of Yakutsk, the horse herders, hunters and fishermen in the taiga villages, the reindeer nomads and mammoth tusk hunters on the tundra, the polar researchers stationed indefinitely on Arctic Ocean islands around its mouth.

The Lena Pillars near Sinsk village, Khangalas District, Yakutia

Those islands are thousands of kilometers downriver from Sinsk though. For now the dense taiga hugged the banks of the Lena, to our right making way only for the occasional huddle of log cabins and to our left for the Lena Pillars, their dull limestone starkly contrasted against the deep, dark green of the the towering river banks that rose behind them.

Eventually Sinsk came into view, a collection of log cabins beginning at the point where the River Sinyaya flowed into the Lena to our right and continuing for perhaps a kilometer along the top of the raised banks of the Lena. Away from the banks the land on which Sinsk was built climbed steeply upwards, giving us a good view of the village as we approached by boat.

House in Sinsk village, Khangalas District, Yakutia

If one continues 50km down the River Sinyaya, so shallow that this is possible by motorboat only for a brief period during the high water after the ice melts, one reaches the Sinsk Pillars, more beautiful than the Lena Pillars but much harder to access. That, however, is a story for another time…

We disembarked, climbed up the muddy bank and were met by Katya’s father and uncle in one of the old grey Uaz vehicles that are seen so often all over remote parts of Russia and the former USSR. We drove down the muddy track that led through the centre of the village until we came to the house that Katya had grown up in, idyllically situated on the high right bank of the Lena. We passed through the gate in the picket fence, walked past the log pile 6 feet high and hundred feet long, through potato fields until we reached the front door. To the left was another picket fence marking the edge of the garden. Beyond the fence the ground dropped away sharply, providing a spectacular view over fields full of grazing horses, mud flats, a huge island that locals use for hunting and berry picking and the towering left bank of the river several kilometers away.

View from Katya’s parents’ house in Sinsk village, Khangalas District, Yakutia

Upon entering, as usual, a huge display of food created us which had somehow been timed to be ready at the exact moment of our arrival. Meat from local horses, cream and butter from local cows, jams from locally collected berries, locally baked-bread, home-cooked pancakes, potatoes grown in the garden and more. All “ecologically clean”, as any Yakut host will be bound to proudly impress on their guests, and all appropriately stodgy for people who do a lot of physical work and spend a lot of time outdoors in the coldest inhabited part of the world. For people who do not, however, it is enough to make you put on several kilograms within quite a short stay, particularly if you have sit down meals four or five times a day as often happens.

And so began our 10 days in Sinsk. What followed was an incredibly relaxing time away from the internet and social media, doing a lot of reading, trying to eat as little as possible of the mouth-wateringly delicious food and occasionally helping the in-laws in the potato field, building a new fence or other small tasks.

Going to collect berries on the island , Sinsk village, Khangalas District, Yakutia

At first it was cold and windy, which thankfully meant no mosquitoes, but after five days the temperature suddenly shot up to 33°C, which meant they and the midges came out in full force. It was light throughout the night it was possible to admire the view at any time, provided one was not attacked by swarms of flying, stinging critters. I would often stand at the back picket fence, watching the herds of horses slowly graze their way across the fields, listening to them splash through streams and puddles when watering, all undisturbed by the noise of engines or people.

I must say I find the lack of internet somewhat less relaxing than I did five years ago. Back then my tour business had not taken off to the extent it now has and I could comfortably take time off from the web without worrying too much. These days, however, there will invariably be a dozen people trying to get hold of me. And in Sinsk the internet teases you. There is one mobile operator, Megafon, who, if you buy a local SIM card in Yakutsk, will provide that little letter “E” at the top of your phone’s screen that indicates the weakest possible level of internet. You still will not receive any messages unless you work out that you can put your phone onto Airplane mode for a few seconds then turn it off again and at some point over the next couple of hours a load of WhatsApp messages and emails will download. Nothing else, no Facebook or Vyber, just WhatsApp and email, and it takes about 24 hours to send a reply to any of those messages.

Rock paintings on the Lena River cliffs near Sinsk village, Khangalas District, Yakutia

What this means is that, instead of having no internet at all and just “getting away from it all”, you end up torturing yourself in an endless battle to download and reply to urgent messages from the outside world. One could of course just not purchase that Megafon SIM card in Yakutsk at the beginning of the trip, but one is stupid, an addict and a slave to the world wide web so one does it every time anyway.

SInsk has a lot to recommend it for tourism. It stands on the confluence of the Lena and the Sinyaya, two rivers with Yakutia’s most spectacular forests of rock pillars lining their banks. It is a particularly quaint village made up mostly of log cabins with spectacular views from either above or below. From a cultural point of view it is also interesting, as many of the inhabitants still practice traditional Yakut horse herding and, in winter, can be seen traveling around the village and its surroundings on wooden horse-drawn sledges.

Sacred shamanic site near the Lena Pillars

Interestingly, there are to this day Russian people in Sinsk who have taken up the traditional Yakut activity of horse herding and speak better Yakut (a Turkic language completely unintelligible to Russian speakers) than Russian. Yakut was the only Siberian language which, even after the Russian conquest of Siberia, was actually picked up by some Russians who settled in the area. While some other Siberian languages died out, Yakut flourished and is today spoken as a first language by most Yakut and even by a few Russians in remote villages like Sinsk.

I, however, did not plan on staying that long. We left after ten days, fully refreshed and prepared to deal with the evils of social media and the net once again.

Practical information:

Getting there: There is no public transport to Sinsk and no accommodation there. It is therefore probably best to visit by ordering a tour, for example through my site Travel Yakutia.

When to visit: The ice road works from December to April. You can access it by boat from June to October.

Not to miss: Lena Pillars, Sinsk Pillars, rock paintings, indigenous horse herders.

Extras: As a detour, in winter it is quite easy to visit Buluus glacier by driving across the Lena on the way from Yakutsk to Sinsk.

Ice tunnel below the Buluus glacier, Yakutia

Posted in Blog.

Ysyakh festival in Yakutia

Opening ceremony at Yskyakh festival

When winter lasts nine months and temperatures hit the -70sC, you’d be forgiven for getting a bit over-excited about the arrival of summer. And thus it is with Siberia’s indigenous Yakut people who hail from Yakutia, the coldest inhabited part of the world. In a republic the size of India but with a population of only one million, 300,000 turn up for the annual Ysyakh festival near the capital Yakutsk to celebrate the brief rebirth of nature after the long freeze.

To enter the festival grounds one passes through a passage lined by ladies in traditional Yakut dress who wave horse-hair fly swats at passers by and call out words of blessing.

Why horse hair and why fly swats? Horses are considered sacred by the Yakut people. While many other Siberian indigenous people at these latitudes are reindeer herders, the Yakuts only migrated here 1000 years ago from Lake Baikal in the south, bringing their horses and cows with them. They never domesticated reindeer, and horse herding to this day remains their traditional way of life. The Yakut gods are portrayed riding horses while demons are portrayed riding bulls, the bringers of cold and winter.

Ysyakh festival opening ceremony

Horse-hair fly swats are considered somewhat sacred and are hung up in many homes to ward off evil spirits. Why did a fly-swat ever become a sacred object? If you had spent a summer in Yakutia, being attacked by mosquitoes, midges and botflies in numbers greater than in any jungle or swamp on the planet, you would understand why.

The only thing worse than winter in Yakutia is summer in Yakutia, a friend once quipped. That is a bit of an exaggeration, as summer is fine if you have good repellent and winter is perfectly comfortable if you have warm clothing, but there is an element of truth there nonetheless.

Today, being right at the beginning of summer, there were thankfully not too many mosquitoes around. The main sources of discomfort were the +31C heat and the ever-present dust. Huge amounts of dust is not something I had ever noticed in Yakutia before but the festival seems to take place in a particularly dusty locale. Shoes, clothing and exposed skin were soon darkening with it. It was a very minor discomfort though, all things considered, and there was so much else going on that the heat and the dust were barely noticeable.

Opening ceremony at Ysyakh festival

After entering the festival grounds you are presented with a handful of horse hair (how many horses did they have to shave to provide this to 300,000 visitors?). You are then blessed and cleansed by another woman with a fly swat and instructed to dip your horse hair in oil then feed it to one of several permanently burning fires nearby as an offering. After walking clockwise around the fire three times you are free to continue on into the festival.

We had aimed to be there in time to watch the opening ceremony, which began at 11:30am. We had set out in our hired car from our rented apartment in Yakutsk at 10:30am, Google Maps assuring us that it would take only 33 minutes to get there, and had arrived just as the opening ceremony was finishing at 12:30pm. Set out early when heading to Ysyakh as there is only one road that leads in the right direction and it is chockablock.

What little we saw of the opening ceremony was quite spectacular though. Hundreds of Yakuts in bright white costumes danced in the sweltering heat, men trying various ceremonious ways to offer kymys (fermented mare’s milk) in chorons (vessels for drinking fermented mare’s milk from) to women who always managed to ignore them, either by dancing on past or raising their outstretched arms and beaming smiles towards the sky in appreciation of the sun.

Osokhay dancing at Ysyakh festival

When it ended, the spectators were let loose, spilling onto the huge grassy plane, mixing with the dancers and forming several concentric rings by linking hands with one another. A booming voice began to chant in the Yakut language, as incomprehensible to Russian speakers as Native American tongues are to anglophones. The people forming the rings began to sidestep to their left and the rings began rotating clockwise around a tall wooden serge, a sacred and traditionally carved horse-tethering pole with a choron on top. This was the ancient spectacle of the Osokhay dance, which I had witnessed and taken part in many times before but never on this scale.

I began photographing but was quickly driven backwards by floods of people pouring in to join the Osokhay. Concentric rings of human beings rapidly spread outwards until I was at least fifty meres back from where I had previously been standing. By now there were around 15,000 people dancing the Osokhay. The concentric rings were so tightly packed together that one had the impression of a single gigantic wheel rotating on an axis formed by the central serge. Unable to take any meaningful photos of something on this scale, I put my camera away and joined in.

After the Osokhay we joined the crowds of people perusing kiosks, cafes and food stands offering traditional Yakut delights such as stuffed perch, olyadushki pancakes and skewers of barbecued horse meat. We wandered the grounds, observing a multitude of traditional dances, sporting events, concerts and rituals and passing hundreds of tents, pavilions, stages, log cabins, enclosures and traditional indigenous dwellings, many with their own mini-festival taking place inside.

Mas wrestling, a favorite Yakutian sport, at Ysyakh festival

The grounds were absolutely enormous and it took at least twenty minutes to walk from one side to the other even if you were not stopping anywhere on the way. There were very few signs or maps and of course absolutely no information in English. If planning a visit it is definitely worth finding out in advance what you want to see and where it will be taking place. Likewise it is worth having a space where you can go to sit down, relax and get away from it all every now and then, whether this be a tent or a car. A car of course has the advantages that a) you can bring way more stuff with you and b) you can do what we did around 3pm – make the long trek back to your vehicle and sit down with the AC on to escape from the heat and dust for a while. You can also use it to store several 5-litre bottles of water both for drinking and for washing the dust off your skin.

By 6pm we were back at the festival to watch one of the main events of the day: the horse racing. Unlike at such events back home in England there was no Tote, no endless row of bookies calling out near-identical odds and no beer tent (the whole of Ysyakh is alcohol-free, so bring your own if it will be required). The only way to place bets was through privateers. In our part of the crowd this meant a pair of sly old ladies who constantly made the rounds through the spectators asking if anyone fancied a flutter on the next race.

The trouble was that there were no odds, and when I asked them what the odds were on a certain horse they did not even understand the Russian word for «odds», looking at me as if I was barking mad. Instead you just chose a horse, bet 500 rubles on it and if your horse came first then you won all the money in the pot.

Musical performance before the horse racing at Ysyakh festival

«I’ll bet on Ataman then,» I said, offering them 500 rubles, having liked Ataman’s description, appearance and name, which means something like a warlord among the fierce Cossack people of southern Russia who had been the first to invade Siberia from Russia back in the 16th Century.

«Ataman’s taken, I’m afraid,» one of the women promptly replied. «The only one left is Wet Chicken,» she apologized. I fail to recall the actual name of the horse she was proposing, but it was something that inspired a similar level of confidence to «Wet Chicken». I went along just for fun, although with hindsight it was easy to see how their scheme worked – they knew the horses well, took bets only on the ones that had no chance of winning and claimed that the favorite was already taken by another better. As there were no bookies or official odds, anyone who did not know the horses well could potentially be convinced into betting on a no-hoper.

Predictably, Wet Chicken limped in far behind all the other horses, almost having been lapped by the winner Ataman.

The horses in the last race galloped past the finish line at around 11pm, their dark figures outlined against a sky the color of molten metal. By now it was around +15C and very windy. Having not dressed appropriately for such weather we purchased some barbecued meat and went back to the car to feed, have a tipple and warm up before the main event – greeting the rising sun at 2am.

Greeting the rising sun at Ysyakh festival

Although it never gets dark at this time of year, Yakutsk is not in the Arctic so the sun does dip slightly below the horizon for a few hours in the middle of the night. In that twilight, the sky looking the way it does on most English summer afternoons, thousands of people stood on a hilltop next to a huge copper serge and waited.

Glowing red streaks slowly spread across the sky around the outlines of clouds in the east. People began to raise their arms with palms facing outwards to soak up solar energy, building up reserves for the vitamin-D starvation of the long winter. Many also held their hands to the metal serge, absorbing energy it channeled to them. As a dim red ball arose, partly obscured by the thick clouds, anyone whose hands had been dangling at their side now lifted them to the heavens and held them there as the sun rose higher.

At some point a booming voice called everyone down the hill to a level area for Osokhay, the sacred Yakut dance of people holding hands in a ring like the sun. As during the festival’s opening ceremony earlier that day, there were so many dancers that a huge number of concentric rings were formed, rotating like a wheel as the booming voice improvised a almost monotone chant in the Yakut language to which the Osokhay dancers sang along.

Greeting the rising sun at Ysyakh festival

There was something incredibly touching about seeing vast numbers of people showing such appreciation for things taken for granted in so much of the world: warmth, summer and the sun.

Around 4:30am we headed back to the car for a few hours sleep on the reclining front seats before heading back to the festival in the morning. We wandered around for an hour or so before sitting down to watch the sporting competitions – running, archery, wrestling and so on. But a lack of sleep, combined with the fact that most of what we were seeing today were less impressive repetitions of events we had seen on the first day, made me want to head for home.

Many of the unique and extraordinary things I saw and experienced on the first day of Ysyakh left such impressions that I will never forget them. If we had had a decent tent to sleep in I would have happily stayed until the evening on Day Two, but in the end sleep deprivation won out and we left at around 4pm.

Greeting the rising sun at Ysyakh festival

When: A weekend after the 20th June

Where: Us-Khatyn near Yakutsk

Price: Free entry

Getting there and away: Regular buses from Yakutsk depart to the festival and cost 45 rubles (2019). They have Ysyakh (Ысыах) written on a sign in their windows. They are old, horrendously overcrowded and not air conditioned. Having to spend 2+ hours standing in one of these in +30sC heat might not be to everyone’s taste. Taxis are a good alternative, although they are likely to hike their prices up to around 2000 rubles due to congestion on the way to the festival. Uber works in Yakutsk, as do InDriver and Yandex Taxi. Alternatively you can hire a car, as we did, for 2000 – 2500 rubles per day, although you will need Russian language skills and the patience to phone around multiple rental agencies who will not give you a definite answer until the last minute.

What to bring: Even if only staying until the greeting of the sun, a tent is a good idea as it gives you somewhere to relax, catch 40 winks and generally escape from it all every now and then. A car and a tent is the ideal combo, as the car means you have AC during the day, which can be extremely hot. A good supply of water for washing of dust is a good idea, plus potentially insect repellant in case there are lots of mosquitoes. If you do not have a car you should have a Russia SIM card to be able to use taxi apps and a translator app to be able to ask people the way to events at the festival. If staying the night, ear plugs would be great plus a sleep mask, as it does not get dark at night.

Not to miss: The opening ceremony, the sporting events, the horse racing and the greeting of the sun.

Posted in Blog.

Sudan

Trader at a camel market in the desert near Omdurman, Sudan

Travelling through Sudan in Ramadan in +47°C while the country was in revolution is an experience I recall about with mixed emotions. Mostly positive of course – this was my second trip to Sudan and as before, literally every single person I met could be counted among the kindest, friendliest, most helpful ever. Everywhere you go, people offer to show you the way, invite you to their home, introduce you to their friends and so on. Of the 80+ countries I have visited I have only every encountered this level of genuine hospitality in four others – Vanuatu, Federated States of Micronesia, Papua New Guinea and Tajikistan.

This time I had entered Sudan from Egypt, but on my previous visit I had entered from Ethiopia. You meet very few other travelers in Sudan, but the genuine consensus in the blogosphere is that while Ethiopia has loads of tourist sites, from the locals you get loads of hassle, while in Sudan there are very few tourist sites but half the pleasure of travelling there is all the incredible experiences you have with the locals. I could not agree more. I don’t want to diss the Ethiopians, but the vast majority of interactions you have there as a traveller involve people trying to get money out of you. I’m 100% sure that this is ONLY the people involved in the tourism industry and not the vast majority of Ethiopians, and is only to be expected in a country where tourism is managed in a way that thousands of rich white people flood in, obviously spending lots of money of which very little filters down to the locals.

But I digress. The weekly ferry down the River Nile from Aswan (Egypt) to Wadi Haifa (Sudan) is a great introduction to the country. Since many of the Sudanese you meet here are people with some experience of international travel, at least to Egypt, a larger proportion know English than in the rest of Sudan. Many approached me as the only non-local to strike up conversations. Over the 18-hour ferry journey I met nearly everyone on the boat, got invited for strong Sudanese coffee and had long political discussions with numerous people about the current revolution and the sit-in protest that had been going on for 1.5 months outside military headquarters. The previous dictator had recently been removed in a coup but the people, worried that a new military dictatorship would simply take over from the old one, were peacefully insisting on a civilian government. Everyone I met was full of optimism and hope for the future. There was a real sense of triumph just around the corner, that this time everything would be different.

Boat on the Nile River, seen from the Aswan – Wadi Haifa ferry

“You’re not worried that they’ll disperse the sit-in with violence?” I asked one guy on the boat.

“They can’t,” he replied confidently. “This time the whole world is watching Sudan. They have no choice but to negotiate with us.”

Having naively not attempted to book a ticket in advance I had been too late to get a bed in a cabin and instead had to down in the hold on benches with all the other cheapskates. They seemed to have put the air conditioning on the “Arctic Siberia” setting, and while everyone else had known to bring blankets with them I had not. I fell asleep shivering and teeth chattering. Enjoy this part of the trip if you ever take this ferry – it will be your last chance to escape from the oppressive heat until you reach Khartoum.

The contrast between Aswan, with its Corniche, 14-storey hotels hotels, swimming pools and traffic, and Wadi Haifa could not be more stark. The Sudanese “town” is little more than a collection of single-story mud and concrete buildings, half consumed by the desert and with sand for streets. I took a motorcycle taxi to a nearby hotel where beds were just over $1. Other than the fact that one of the walls in my room was collapsing it looked like an OK place to stay.

Wadi Haifa

The temperature was 47°C so I went to take a shower in a row of outdoor cubicles just a few feet from my room. While doing so a cockroach appeared out of a whole in the wall. Having travelled all over Indonesia by Pelni ferry I now have a raw and raging hatred for these creatures. I splashed water at it in the hope it would disappear back into the hole but instead it scurried down the wall and stopped in a corner on the floor. I continued with my shower, nonetheless keeping a watchful eye on the little critter.

When a second cockroach appeared from the same hole I was very close to the limit of what I was comfortable with and decided to finish my shower and get the hell out. I washed the soap off my body, glanced back at the hole and found that I was suddenly in that scene from Arachnophobia when the spiders start getting born with reproductive organs and begin multiplying exponentially. Dozens upon dozens of cockroaches were streaming out of the hole, attracted by god knows what, to cover the wall of the shower.

With a curse I grabbed my towel, grappled with the lock on the door and burst out into the sand and blazing sunlight, almost knocking over a man who had been washing his feet just outside. He froze, hands unmoving on soapy feet, staring horrified at me as I realized that in my hurry I had not completely covered my back side with the towel. Apologizing, I stumbled towards my door, fumbled with the padlock, gained access and shut it rapidly behind me in shame.

Wadi Haifa’s sandy streets were deserted during the day, its single-storey buildings providing no shade from the scorching overhead sun. Locals, forbidden from eating or drinking, could occasionally be glimpsed through open windows, lying around in the dark of their houses, trying to expend as few calories as possible and prevent themselves from sweating.

At around 18:30, however, the town came alive. Hundreds of people poured of their homes and every second building turned out to be a restaurant or hookah cafe. Both sides of every street were suddenly lined with chairs placed in the sand, every one of them occupied by someone eating, smoking shisha, drinking strong Sudanese coffee with ginger, talking, relaxing, enjoying the twilight after the trial of the day.

The next morning I spent hours waiting around for a minivan going south to Dongola, eventually arriving there in the afternoon. A motorcycle taxi driver took me to a huge modern hotel, spectacularly out of place and by far the best-looking hotel I saw anywhere in Sudan, including Khartoum. What it was doing here in Dongola I had no idea, but I welcomed the thought of a decent room after Wadi Haifa and the ferry so I went inside to investigate.

The lobby was empty, the restaurant was empty, the lifts were not working and the place seemed utterly deserted. Not only that, but everything had been left exactly as it has presumably been when the place had been working. I walked around, ascended to the forth floor, shouted, but could not find anyone. Bemused, I asked the driver to take me to another hotel.

Fifteen minutes later we had checked every hotel in town and all were full. I asked him to take me back to the big modern hotel, thinking that either I would find someone there this time or just sleep on a sofa somewhere. Right enough, this time I chanced to open an unlocked door to find four men inside, lounging around on mattresses on the floor and trying to keep cool.

“There are no rooms,” they told me, after I had shown them how to use Google Translate on my iPhone.

“But the hotel is empty,” I said, “Are you sure I cannot have a room?”

“We can give you a room, but they are in a bad condition,” he said.

The room was big, modern, with a nice bed, a cupboard, and by far the best room I would have anywhere in Sudan. It cost $5 and had a visible layer of dust over everything, as though it had not been cleaned in a long time, but beggars can’t be choosers. It did make me wonder what such a hotel was doing in this tiny remote desert town. It couldn’t possibly be economically viable for a private businessman to run so must have been built by the government for some reason. Given the recent overthrow of Sudan’s 30-year dictatorship and ongoing revolution against the military junta that had replaced it, one could see why a government-run hotel might be allowed to slip into disuse. Which raised the question: just how much of the government, public services and the country in general was actually functioning right now? Was there a police force? Were school teachers still getting paid? Could one get medical care?

The next morning was also spent waiting around for a minivan heading south to fill up with passengers. This seems to be an integral part of travel in Sudan. The drive was not as long as the previous day though, and I arrived in Karima by 12:30.

I found a motorcycle taxi and went out of town to Karima’s pyramids, standing in the desert several hundred meters from the roadside. They were not quite as impressive as the ones I had seen in January at Meroe, but were well worth a look (see the background of this web page for a general impression!).

From here I started trekking across the desert towards Jebel Barkal, a table-top hill perhaps 100 meters high and a kilometer or so from the pyramids. Upon arrival at the slope I had already drunk half of my two-liter bottle of water, sweated a prodigious amount and realized that I had left my hat in my rucksack at the bus station. I had to make a decision whether to go ahead with this climb, at 1pm with 46°C heat, scorching overhead sun, no shade, no hat and little water. I decided to go ahead with it. I cannot decided whether it was the right or wrong decision. I certainly suffered a bit from it, it was certainly a bit risky, but it was only a short climb and the suffering did not go on too long.

Karima, as seen from the top of Jebel Barkal

There was no path up the hill, just a very steep slope covered with rocks and sand to scramble up to the top. Once I was on the plateau at the top there was a spectacular view of the surrounding dunes, pyramids, Karima and the Nile. From up here it was immediately very clear why civilizations had grown up around the Nile and why it was to this day so important for the region: all you could see in every direction was endless orangey-yellow sand, but it was broken broken in one place by a narrow band of greenery that snaked through it along the banks of the river. In the vast desert, the Nile was the only thing that made life possible, as well as providing a means of transport from here north to the Mediterranean or south to Ethiopia and Uganda.

It took me a while to find the way back down, as from the edge of the plateau the slope looked almost like a sheer cliff. Once I was on the slope, however, I found that it was too steep to descend on foot but that when you tried to do it on your bum and hands the rocks and ground were too hot to touch. This led to a very rough descent with several near-burns until it leveled out and I was able to continue on foot, my water by now all long-gone and the sweat pouring off me in cascades.

The road looked tantalizingly close from the bottom but it took a long fifteen minutes to get there, and I believe this was the closest I have ever come to sunstroke or heat exhaustion. Once there I flagged down a passing vehicle that took me back into town. What to take away from this situation? Climb Jebel Barkal in the evening and enjoy the sunset, do not try it in the middle of the day with no hat and insufficient water!

I caught another minivan headed east to Atbara. By around 18:30 we were approaching town and I noticed that there were an unusual amount of people hanging around the roadside. A bit further on some of them had formed a roadblock, forcing our driver to stop. The driver wound down his window and proceeded to speak with the men from the roadblock for around five minutes, sounding as if he were explaining something in an apologetic tone. Eventually the road block guys smiled, let him go and waved him on.

“They want us to break our fast with them,” the driver told me. I had been convinced it was in some way connected to the revolution, but as we drove on more and more people continued to run up to our car, trying to wave us over to the side of the road where many of them had laid table cloths with bread, water and other food around which large groups were sitting and eating.

“They’re selling food like a cafe?” I asked the driver.

“No, this is just what everyone does from small villages along the road or nomad camps off in the desert. They come to the road and share all their food with each other and any passersby who want to join in.”

I spent the night in Atbara in a mosquito-filled room, sweating endlessly.

The next morning I found a driver willing to take me to the archaeological sites of Naqa and Musawwarat. While many of Sudan’s sites can be accessed by public transport, such as Karima and Meroe Pyramids, these two cannot as they are 30km or so off the main road in the middle of the desert.

Naqa

Driving through the desert, we passed nomadic people once every ten minutes on average, traveling by donkey, camel or just watering their animals at a well. There was not a single permanent settlement. It definitely provided a very different impression of Sudan from what I had seen so far. Just following the main road through the country from tourist site to tourist site, one might be tempted to think Sudan was just a string of villages and towns clinging to the road. As soon as you leave it, however, you see that things are very different just a few kilometers away, with very few buildings but plenty of life and human activity in all directions. It certainly made me wonder, if one turned off perpendicular to the main highway and just drove, how far through this roadless nomad country would one travel before reaching the next signs of settlement or construction of any sort? Judging by the maps, quite a long way.

Nomads at a well near Naqa

Naqa with its lion statues and Musawwarat with its forest of crumbling pillars were delightful, but the real highlight for me was getting a brief glimpse of Sudan away from the road. An even greater highlight of the day was arriving in Khartoum in the evening, having dodged the crowds off roadside fast-breakers on the outskirts and finally having a room with air-conditioning to sleep in! The cold was just heavenly as I dozed off to sleep, promising myself that I would never subject myself to such tortuous levels of heat ever again.

Musawwarat

The next day, being Saturday, there was supposed to be a camel market taking place in the desert outside the nearby town of Omdurman. I crossed Khartoum, noticing several pickup trucks parked on a bridge and loaded with mounted guns far longer than an adult person. Although the revolution was currently focused around a peaceful sit-in demonstration, the opportunity for violence was right there, ready and waiting.

Camel market in the desert outside Omdurman

I have seen camel markets before, having spent a lot of time in Oman in the 1990s as a child. They were absolutely nothing, however, compared to this one. There were literally thousands of camels, divided into several different herds, occupying a vast area of desert outside the town. Occasionally a herder would drive his animals to a well to water them, a new herd would arrive over the horizon in cloud of dust and sand, and potential buyers wound their way amongst the produce, inspecting one camel after another and creating a constant sense of movement on the desert plane. A helpful passerby explained to me that one area was for meat camels, another was for transport camels and a third was for racing camels, but of course to an outside eye it was hard to tell the difference between the types.

Camel market in the desert outside Omdurman

I flew out of Sudan the next day, glad to be escaping the heat but still just as much in love with the country as I had been after my first visit, determined to come back to visit the west if the situation there ever improved. I also allowed myself to share in the quiet optimism of the Sudanese for the future of their country, perhaps naively hoping they might lead the way for other African nations with a shining example of how to build a democracy from a broken dictatorship.

Camel market in the desert outside Omdurman

Practical information:

1. Visa. Easy to get. You just need to provide flights and a hotel booking to your nearest Sudanese Embassy. Alternatively certain Khartoum hotels, such as the Accropole, can arrange for you to receive a visa on Arrival at Khartoum Airport if you book their hotel.

2. Money. You can easily get by on $10 – $12 a day if willing to sleep in cheap hotels. This will cover your accommodation, food and water and transport.

3. Safety. After months of peaceful protests there was a sickening massacre of hundreds of people on June 3rd 2019, a few days after I left. Since then, however, everything has been calm and the military junta and the civilian opposition seem to have finally reached an agreement about how Sudan should be governed in the future.

4. TransportThere is transport at least daily between all the main villages on the main highway that dissects Sudan from north to south. Sudan is one of those countries where you can just ask around and everyone will be willing to help you find transport or at least show you to the bus station.

5. Accommodation.As hinted at in this book, accommodation standards are extremely low, especially in smaller towns. They are also very cheap. For $1 to $1.50 you can get a bed in a dorm like the one I described in Wadi Haifa. For $5 – $7 you can get a single or twin room in an actual hotel where everything is a bit dirty and rough-looking but which is basically completely comfortable. Only in Khartoum can you find anything of a slightly higher standard.

6. Ferry between Egypt and Sudan. This departs Aswan on Sunday and Wadi Haifa on Tuesday. Book in advance if possible as otherwise, like me, you may end up having to sleep in the hold on a bench with a hundred or so other passengers. See my Egypt blog for more information.

Camel market in the desert outside Omdurman

Posted in Blog.

Egypt

Every year in May, having spent the winter season freezing up in Arctic Siberia, the first thing I do is to have a “do nothing” holiday somewhere warm in a nice hotel on the beach. There are no roads in much of Siberia but about a million rivers, which you can drive on in winter and which make getting around much easier. Mid-November to early May, when ice is thick enough to drive on, is therefore our busiest season. In mid-May we suddenly have almost nothing to do, as the ice roads disappear, real roads turn to muddy sludge, and driving off-road becomes like driving through an extra-deep swamp of slushy melting snow and earth.

But this blog is supposed to be about Egypt, not Arctic Siberia.

I took my first “do-nothing” holiday six years ago, aged 29. Before that, oddly enough, it had never even occurred to me to spend money going to another country to do nothing. Beaches, the sea and anything associated with them held very little appeal. Bit by bit, however, working in Arctic Siberia corrupted me, making warmth and doing nothing seem more and more attractive.

In truth, I rarely do the purist “do-nothing” thing any more, as it gets intensely boring. What I actually want after the hectic exhaustion of the winter season is a nice hotel, a good beach, as little transport as possible and a few of my favorite leisure activities thrown into the laziness of the trip to make it more interesting and, actually, even more relaxing.

Egypt seemed like the perfect choice – not too far from Russia, great all-inclusive hotels for cheap rates, plus some of the best snorkeling and archeological sites in the world. After a week of that, I thought, I should be fully refreshed and ready for some more actual travel.

Pool at Sunrise Montemare Resort, Sharm el Sheikh

On 17th May my wife Katya and I checked into a room with its own balcony and attached private swimming pool just meters from the sea in the Sunrise Montemare Hotel, Sharm el Sheikh. We had picked out the hotel as it was supposed to be located in one of Sharm’s best snorkeling areas, and we were not disappointed.

I had read previously about three great snorkeling areas in and around Sharm el Sheikh. I checked them all out and will quickly review them here:

1. The stretch of coast where the Sunrise Montemare hotel is located. This exceeded all my expectations. It was the best snorkeling I saw in Sharm el Sheikh and some of the best I have seen in the world. I have been to some of Indonesia’s best snorkeling sites such as Raja Ampat and Nusalaut, plus Belize’s Northern Cayes and other great snorkeling areas. This was not comparable to the best sites in Raja Ampat or Belize, needless to say. However, the off-beach snorkeling here was almost as good as the off-beach snorkeling on Kri, one of Raja Ampat’s best snorkeling islands, minus the turtles and sharks you get on Kri but plus a manta ray, which I had still never seen before this! I swam around 1km to the left and 1km to the right of the hotel’s beach and was constantly surrounded by large numbers of multi-colored fish.

Snorkeling off the beach in Sharm el Sheikh

2. Tiran Island. A small island with some amazing offshore reefs. It actually belongs to Saudi Arabia but tourists from Sharm el Sheikh can visit without a visa and all hotels sell trips there. Lots of fish and a few rays, but the snorkeling off Sunrise Montemare’s beach was better!

Snorkeling at Tiran Island, Saudi Arabia, accessed from Sharm el Sheikh

3. El Fanar and Ras Um Sid. These are just around a small headland from Sunrise Montemare Hotel. I didn’t try swimming there from the hotel because nobody could tell me what the currents were like on the way, but it is only a 10-minute walk down the road anyway. They are reputed to be among the best places to snorkel in Sharm el Sheikh. In my experience swimming from El Fanar to Ras Um Sid they were good, but the stretch of beach mentioned above in point 1 was better.

Coral near El Fanar, Sharm el Sheikh

After a week of snorkeling, beach bumming, lounging by the pool, drinking the hotel’s unlimited free cocktails and generally loafing around in heat that was usually between 40°C and 44°C I was fully revitalized and ready to move on. A flight to Cairo then an overnight train to Aswan and I was almost ready to cross into Sudan on my own, Katya having been unwilling to join me on a trip to an African country in open revolution.

But I had a day until the 18-hour Nile River ferry to Sudan departed and while here it would have been criminal not to visit one of Egypt’s most spectacular archaeological sites: Abu Simbel. All hotels in Aswan sell tickets on bus tours to Abu Simbel, during which you apparently get off the bus and barge your way through swarming crowds of likeminded cheapskates to get a look at the temples. The buses arrive at 8am and leave at 10am, so if you want the temples to yourself all you have to do is arrive after this time.

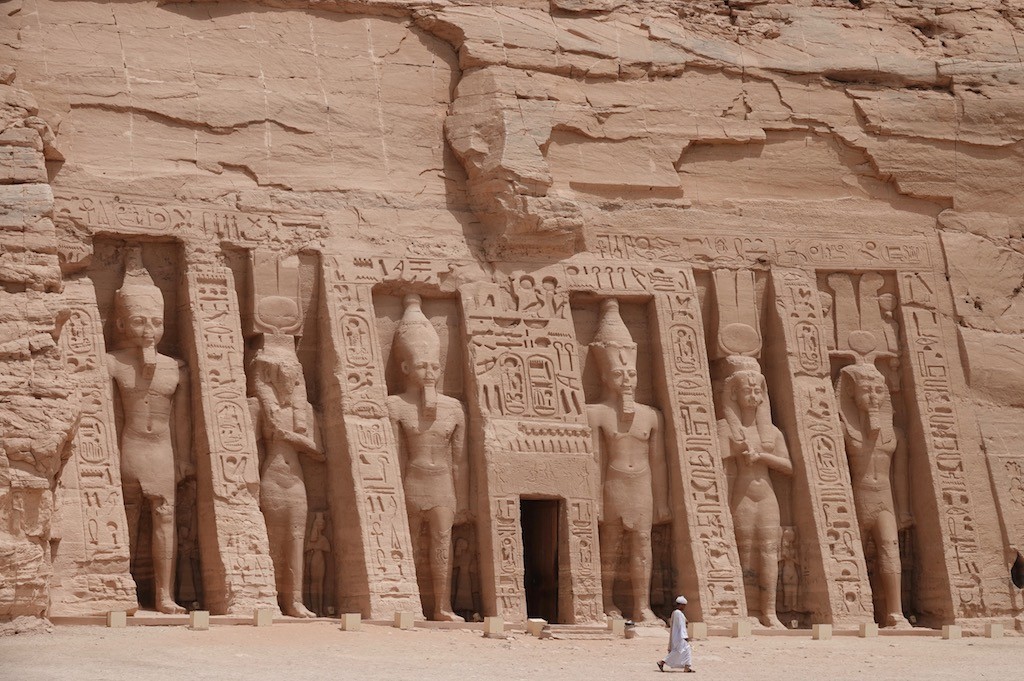

Abu Simbel

That is exactly what I did, hiring a car and driver for a very reasonable price and arriving after the crowds. I am not going to write a long beautiful description as the pictures say it all, and I cannot recount much of the history of the place as I do not know it. Suffice it to say that the gargantuan statues carved thousands of years ago were pretty awe-inspiring.

The next day I boarded the ferry to Wadi Haifa in Sudan. Here are a few points of advice for anyone else planning to do this:

1. Obviously get a Sudanese visa first.

2. Try to book ahead using an agency if you want a bed in a cabin. I did not do this and had to sleep down in the hold on a bench along with a hundred or so other passengers.

3. Bring a blanket. The air conditioning makes it absolutely freezing.

4. Bring a camera with a good zoom lens. You will sail past Abu Simbel and can get some good photos of it if you have not actually visited.

5. Be friendly. You will most likely be the only foreigner and absolutely everybody who speaks any English will want to come and talk to you.

6. You get free food on board but bring some cash to buy water, coffee or other drinks.

Sleeping area on Nile River ferry from Aswan (Egypt) to Wadi Haifa (Sudan)

Posted in Blog.